Last weekend I got to see a live interview with one of my all-time heroes, Hayao Miyazaki. He said, through a translator, all kinds of interesting things. When asked about computer animation, he had this to say: “One time we hired an expert to animate some scenes on the computer, but in the end we found that we could draw the scenes faster with a pencil.”

Now maybe this was his choice of words, and maybe it was the translator’s, but I found this response pretty revealing. It reflects a thought process about what animation is, in which drawing is central to everything. If what you’re trying to do is draw a scene, a pencil really is faster than a computer. But is that necessarily true? Is animation, at its heart, about drawing?

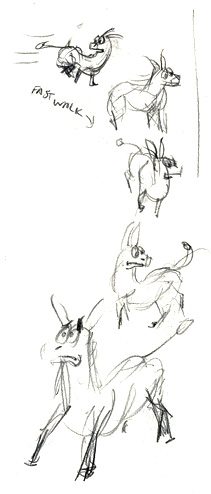

I’ve been animating full-time now for ten years. And for most of those years, drawing was not a major part of my animation process. I drew, of course: life drawing classes on the weekend, sketchbook on the train, and so forth. I would also do thumbnail sketches sometimes for my shots: crude little stick figures of body poses, which I’d use to work out problems like which foot should start a walk in an acting scene. But I never bothered to learn how to really draw the characters I was animating, like a traditional 2D artist would. I genuinely believed that thumbnailing was more than enough drawing skill for my animation needs.

My personal narrative of animation history went something like this: in the olden days, before you could even think of animating, you first had to learn how to draw a character, “on model”, in every possible pose, from every possible angle. You had to hone this skill and master it, and only then could you begin to put your ideas about movement, acting, or personality into your work. This requirement excluded all kinds of talented actors and performers from the field, simply because they had never learned to draw that well. Thanks to the computer, though, the character is always “on model”. So we lucky CG animators no longer have to be able to draw well to animate well. We can think directly in terms of weight, body language, emotion, and so on, and let the computer worry about annoying details like foreshortening, perspective, and wrapping features around a three-dimensional form.

When I started teaching at Animation Mentor, I used the thumbnail concept as a way of making drawing palatable for my students who insisted they couldn’t draw. “You can draw a stick figure, can’t you? That’s fine, start with those!” I would describe it as a system of annotation, like shorthand writing for poses. Treating drawing as a kind of written language seemed to work for the techies and engineers in my classes. It was a great starting point for helping them improve their drawing skills. And it allowed me to continue believing, for a few more years, my little story about how lucky we are to have computers to take away the tedium of drawing all those frames by hand.

I no longer believe this to be true.

What has changed? Well, our rigs, for one. In the 1990’s, CG rigs tended towards the stiff and unwieldy, based on strict interpretations of some abstract anatomical ideal that never came close to the flexibility of a real flesh-and-bone body. They were always “on model” because it was literally impossible to push them off model. The joints would only bend so far, and no further. Nowadays, industry-standard rigs are chock full of fancy stuff: squash and stretch on every facial feature, bendable bones, you name it. Pushing a character off model is not just possible, but very easy. Our rigs have become so flexible that you can make a character look like a completely different person if you put your mind to it.

Which brings us to the second thing that has changed. If it’s so easy to push a rig off model, how do you know when you’ve pushed it too far? When is an expression on model, and when is it not? It’s no longer a matter of what the rig can or can’t do. Now it’s up to you. It’s an aesthetic choice. It’s subjective. It’s a matter of artistic intent. Does it look good? Does it feel like the character himself, or just a distant cousin? The only way to know if a character is on model is to have a clear artistic vision of the character in your mind, like a Platonic ideal, but as infinitely malleable as flesh: an idea of how your character should look. In every pose. From every angle. A mental model, you might call it. Or maybe a mental model sheet.

Perfecting that mental model sheet is exactly what 2D animators were doing when they learned to draw their characters. They were not wasting their time on some rote skill that computers would one day make unnecessary. They were realizing a vision in their heads, using pencil and paper as the vehicle of practice to make it perfect. Drawing, it turns out, was never just a set of mechanical movements forced on the animator by the constraints of the 2D medium. It was a two-way process that enriched the animator’s understanding while also communicating to an audience. These two goals are no less important now than they were fifty years ago. And the simple act of putting pencil to paper, over and over again, may well be the fastest way to achieve them.

When I look at scenes I’ve animated recently, I get the sneaking feeling that somehow they could have been better, but it’s hard to put a finger on what exactly is missing. When I look at scenes I did a few months earlier, the problems are a lot more obvious. And I know exactly what’s wrong with the shots I did five years ago (ugh, don’t get me started!) The difference, I realize now, is that my mental model of the characters has been slowly getting deeper as time passes. If only I’d taken the time to practice drawing those characters, think how much better those older shots would look!

Drawing may not be the only thing animation is about, but it is certainly at the heart of it. That mental model is what makes the difference between okay-looking poses and great ones. And after ten years of letting my drawing skills get rusty from disuse, I realize now that I’ve got a lot of catching up to do. Time to crack open some Walt Stanchfield

, find a nice soft-leaded pencil, and get to work!

Nice post. Wish I could have met Miyazaki, where’d you meet him, at the con?

I didn’t meet Miyazaki one-on-one, he did this talk at Zellerbach Hall in Berkeley. It was him, his translator, and the interviewer on stage, and the rest of us in the audience. Still a great evening!